For decades, Steve Hein has been many things to many people. A masterful wildlife artist, a passionate falconer, a visionary educator, and the founding director of Georgia Southern University’s Center for Wildlife Education. But above all, Hein has been a storyteller: someone who sees life as a series of moments to be trusted, embraced, and shared.

Sitting in his office, surrounded by sketches, keepsakes, and mementos from a lifetime spent close to the natural world, Hein reflects on a journey he never planned, but one he feels was shaped by listening to his heart more than any map.

"I thought I'd be a veterinarian. Maybe run the family business. Maybe something with finance," Hein said. "But I kept choosing the path that made me come alive."

That path would eventually lead him from pencil sketches on crumpled notepads to national recognition as an artist, from quiet walks in the woods to soaring flights over stadiums, and from a simple dream of building a wildlife center to sharing one of the most profound bonds Georgia Southern, and the country, has ever known: the bond between a man and an eagle named Freedom.

Young Steve Hein: A Life Rooted in Nature and Art

From a young age, Steve Hein found himself drawn to two things: nature and creativity. Growing up, he could often be found wandering the outdoors, studying animals, or sitting quietly for hours with a handful of crayons or a sketchbook.

"I was the kid who would sit down with crayons and still be there an hour later," Hein laughed. "It was just natural for me — observing, creating, being still."

His early fascination with the wild world eventually grew into something larger: a deep reverence for wildlife and a desire to capture its spirit through art. Even as Hein pursued a degree in Business Administration at Georgia Southern, the pull toward nature never left him. He spent weekends sketching, hunting with hawks, and immersing himself in the rhythms of the land.

After college, Hein was expected to follow a more traditional path, perhaps running the family business or working in finance. But fate, in the form of a commission to create a painting for Georgia’s then-Governor Joe Frank Harris, intervened. That one painting launched a professional art career that took Hein to the top of the wildlife art world, winning awards, national recognition, and corporate sponsorships.

Building the Center for Wildlife Education

Steve Hein’s vision for a place where people could reconnect with nature took root long before Freedom ever arrived at Georgia Southern. In the mid-1990s, fueled by his passion for wildlife and education, Hein spearheaded the effort to create the Center for Wildlife Education on the university’s campus.

“We had the land. We had the mission. We just needed the right bird,” Hein recalled.

The center officially opened in 1997, occupying a modest four-acre tract. But from the beginning, Hein dreamed bigger. The center would not simply be an exhibit, it would be a living classroom where students, children, and the community could learn firsthand about the natural world.

One of Hein’s earliest goals was to acquire a bald eagle, a living embodiment of the center’s mission and a powerful symbol of America’s wildlife heritage. However, getting a flight-capable, non-releasable eagle would prove to be a long and uncertain process. Hein submitted an application to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, knowing that such birds were exceedingly rare and that others had been waiting far longer than he had.

"We were on a waiting list from day one," Hein said. "And we stayed there for thirteen years."

In the meantime, the Center flourished under Hein’s leadership, offering educational programs, growing its collection of birds of prey, and building a reputation across Georgia. Still, the dream of having a bald eagle and fulfilling the vision of connecting people with nature through such a powerful symbol, remained just out of reach.

Until one day, when the phone finally rang.

Freedom — Arrival, Training, and Becoming a Legend

After thirteen years of patient waiting, in May of 2004, Steve Hein finally received the life-changing call: a young bald eagle with a permanently injured beak, deemed non-releasable, was available for placement. His name would be Freedom.

"I'll never forget the moment," Hein said. "It was joy, excitement, and absolute intimidation all at once."

Although Hein had years of experience handling hawks and falcons through his falconry background, working with an eagle presented a whole new challenge. Eagles are larger, stronger, and far more independent than other birds of prey. Their training requires not just skill, but a profound level of patience, trust, and mutual respect.

Training Freedom was a painstaking three-year journey. Hein approached it methodically, understanding that with a creature of such power and dignity, there was no shortcut. Every interaction was about trust-building. Every step forward had to be earned, not commanded.

And in 2007, Freedom made his first free flight at Paulson Stadium — a soaring symbol not just of Georgia Southern spirit, but of a dream fulfilled.

Together, Steve and Freedom became an inseparable part of the university’s identity. Whether soaring above roaring crowds on football Saturdays, quietly inspiring graduates at commencement, or posing for thousands of photographs with students and families, Freedom wasn’t just an attraction. He was a living embodiment of perseverance, hope, and pride.

Throughout it all, Hein remained steadfast in one principle: the story was never about him. "My job was to make Freedom the star," he said. "I stayed in the background. It was always about the connection between Freedom and the people."

Freedom’s Long Life and Symbolism

Freedom’s life was nothing short of extraordinary. Living to the age of 21, he far surpassed the odds that most bald eagles face in the wild. Steve Hein often explained the rarity of Freedom’s journey, and why it meant so much to so many.

"Fifty percent of bald eagles don't even survive their first year," Hein said. "And only about 10% make it to five years old, when they finally get that iconic white head and tail."

Together, they crafted a legacy that touched tens of thousands of people, becoming more than just a mascot. Freedom became a living symbol of resilience, patriotism, and second chances.

Hein compared standing next to Freedom to standing at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. "You're next to something that means so much to so many," he reflected. "It’s an incredible responsibility."

A Life Captured in Ink and Inspiration

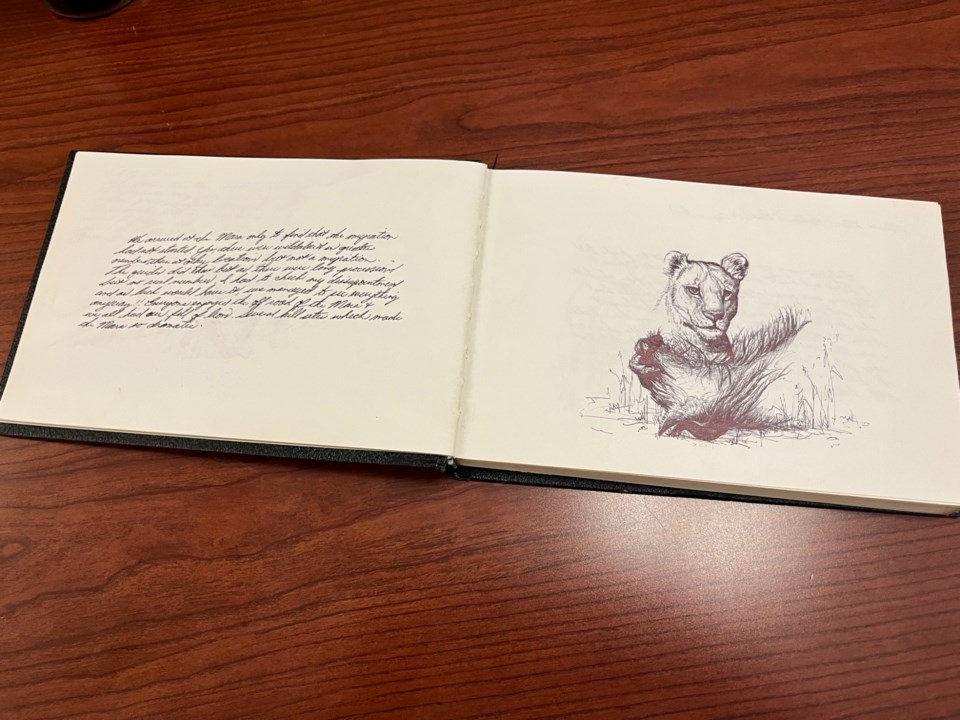

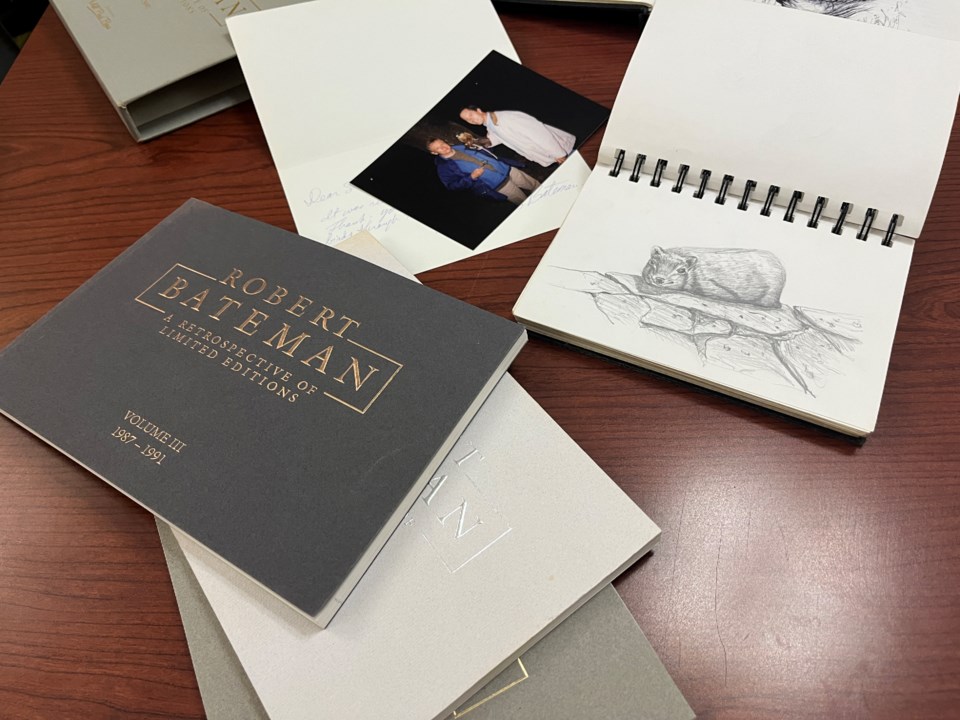

Hein’s office at the Center for Wildlife Education is more than just a workspace, it’s a living reflection of a life deeply tied to art, nature, and storytelling. Everywhere you look, there are hand-drawn sketches, field journals, and artifacts that chart a journey fueled by curiosity and creativity.

Before Freedom entered his life, Hein had already built a reputation as a professional wildlife artist. After graduating with a business degree, he turned away from corporate life and instead pursued what made him feel alive: capturing the beauty of the natural world with pen, pencil, and brush.

“I became a wildlife artist at 23, foregoing becoming a veterinarian,” Hein said. "I started illustrating books, won Ducks Unlimited Artist of the Year three years in a row, won a duck stamp, painted for Coca-Cola, Georgia Power — it all just happened because I stayed open."

Journaling, too, became a deeply personal practice for him. Hein traveled with sketchbooks, filling them with quick field drawings and observations of nature. Whether sketching wildlife in Africa, the Amazon, or the Georgia countryside, each page captured not just what he saw, but how he experienced it.

"Younger people look at my journals now and say, 'Oh my God, it's beautiful,' but also, 'I can't even read your handwriting,'" Hein laughed. "But they were never just for display, they were raw, honest records of a moment."

The artistic influences that shaped him run deep. Hein grew up watching Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom with Jim Fowler, a connection that eventually became real when Fowler helped raise funds for the Wildlife Center. Another of Hein’s heroes was the famed Canadian wildlife artist Robert Bateman, who would later personally encourage Hein’s work with a handwritten letter, a keepsake Hein still treasures.

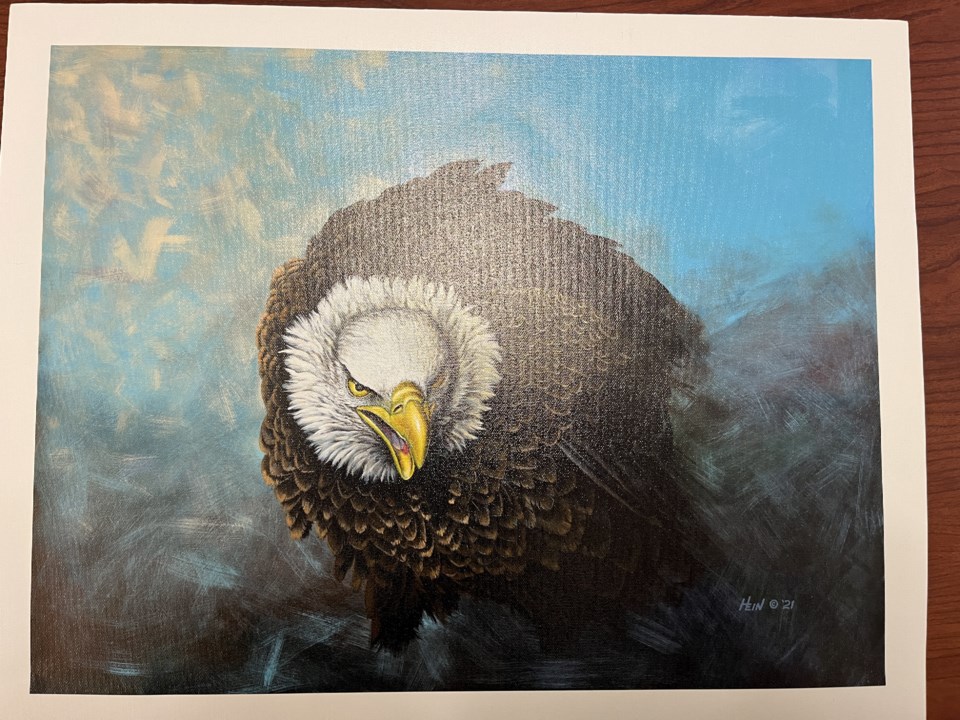

Among all the works in his office, one stands out: a quiet painting of Freedom, drawn entirely from memory and field sketches. Nearby sit Freedom’s training hoods, travel gear, and even the camera rig used when Freedom was featured in a BBC documentary.

"I’m afflicted," Hein said with a smile, speaking of his constant urge to create. "I can’t help it. Whether it’s a pen, a brush, a piece of paper — it’s how I process the world."

A Falconer at Heart

Before Freedom, before the stadium crowds and the televised flights, Steve Hein’s connection to birds of prey was already deeply woven into his life. Long before he became Freedom’s trainer and caretaker, Hein was a falconer, someone who had spent years earning the trust of wild raptors, not by taming them, but by forming a quiet partnership rooted in respect.

Falconry, one of the world’s oldest hunting traditions, demands patience, precision, and an understanding of nature’s rhythms. Hein earned his Master Falconer license early in life, practicing the art with hawks and falcons across the wild open landscapes of Georgia, Kansas, and Wyoming.

"It was always pursuits along the lines of falconry," Hein said. "Hunting out in the outdoors, in the middle of nowhere, not in front of 27,000 screaming fans."

Working with falcons taught Hein lessons he would later carry into his relationship with Freedom. A falconer doesn’t command a bird; they build trust day by day, flight by flight. Every successful hunt or training session is a result of subtle communication — a language without words, where trust must constantly be earned and re-earned.

"You don't domesticate a bird of prey," Hein explained. "You build a partnership. And every day, you respect the wildness that’s still inside them."

When Freedom arrived at the Center, Hein was one of the rare few who truly understood the magnitude of what lay ahead. Training an eagle, a solitary apex predator with immense power and intelligence, would not be like handling a falcon or hawk. It would require even more patience, more listening, more mutual trust.

In many ways, Freedom was never "trained" in the traditional sense. He and Hein built a bond, one that allowed Freedom to choose trust, choose participation, and eventually, choose flight under the stadium lights. It was a relationship that mirrored everything Hein had learned through years of falconry: that the real magic doesn’t happen through control. It happens through connection.

Over the years, Hein’s falconry journey took him around the world — from the plains of Africa to the jungles of the Amazon, from frozen fields in the Midwest to quiet mornings on his own 10-acre farm outside Statesboro. But it was always the same truth that kept him grounded: the greatest privilege was not owning a bird, but being trusted by one.

Family, Leadership, and a Life Beyond the Wildlife Center

While Steve Hein’s story with Freedom captured the public’s heart, it is only one chapter in a much larger life, a life grounded in family, service, and a deep belief in the power of community.

A Georgia Southern graduate with a degree in Business Administration, Hein never imagined that his career would blend business with artistry, falconry, and education. But like every step in his life, he chose the path that felt right, even if it wasn’t the most expected.

His commitment to leadership stretched into the broader community as well. Hein served as past president of the Statesboro Convention and Visitors Bureau, graduated from the Leadership Bulloch, Leadership Southeast Georgia, and Leadership Georgia programs, and eventually chaired Leadership Southeast Georgia.

Yet through every professional success, Hein’s family remained the anchor. He and his wife, Kathy, built a life filled with shared adventure, resilience, and love. Together they raised four children — Adam, Meredith, Colleen, and Mallory.

At home, life was always lively: horses, dogs, falcons, and family members all part of the daily rhythm. Hein’s property outside of Statesboro wasn’t just a residence — it was a living extension of who he was, a place where his love of wildlife, family, and hard work could all coexist.

It’s a legacy built, not in the grand moments alone, but in the steady, quiet ones — where trust is earned, families are nurtured, and the natural world is honored with every choice.

A Symbol That Moved Hearts

Freedom was never just a bald eagle. He was a living embodiment of hope, resilience, and the enduring ideals that the American bald eagle represents. Under Hein’s care, Freedom became more than a fixture at football games, he became a symbol that stirred something deeply personal in thousands of people.

Hein witnessed it time and again: the way people reacted when they stood near Freedom. Some would smile broadly, others would fall silent. And some, often unexpectedly, would break down in tears. It wasn’t simply the majesty of the bird, Hein explained, but what Freedom meant.

"I've had people seeking asylum in the U.S. break down crying when they saw Freedom," Hein said. "One of them kissed him on the shoulder. They didn’t speak English, but through an interpreter, I learned it was because Freedom symbolized hope — the chance for a new life."

Military veterans, families who had lost loved ones, first-generation Americans, all found something profound in Freedom’s presence. For some, it was a connection to the sacrifices they or their loved ones had made. For others, it was a reminder of the freedom they had fought for, or were now embracing for the first time.

Hein made it his personal mission to ensure that these encounters were truly personal. He deliberately stepped out of photographs, encouraged people to frame Freedom alone, and never made himself the center of the experience. "It wasn’t about me," he said. "It was about them, and the connection they were making."

Life Lessons from a Life Well-Lived

If there’s one thread that runs through Steve Hein’s life — from falconry fields to football stadiums — it’s the belief that true living requires trust, vulnerability, and connection.

Over the course of his interview, Hein reflected on the many lessons he’s learned from nature, Freedom, and his own winding journey. But perhaps the most powerful were the ones that don't often make headlines: lessons about being present, taking risks, and choosing real human connection over public attention.

"Our generation touched people at arm’s length," Hein said. "We were face to face. We didn’t have distractions. We were present."

He explained that in today’s world, filled with technology and curated online lives, it's easy to mistake visibility for meaning. But Hein sees it differently.

"Don’t tell me how many Facebook friends you have," he said. "Look me in the eyes and tell me you enjoyed meeting me. That’s what matters."

It’s a lesson he modeled every day at the Wildlife Center, always focusing on creating genuine encounters rather than polished appearances. When people met Freedom, it wasn’t about spectacle, it was about the quiet power of a real, unfiltered moment between a person and a symbol.

Hein also spoke often of trust, not the naive kind, but the brave kind. The kind that understands risk and chooses to be vulnerable anyway.

"To really live," Hein said, "you have to make yourself vulnerable. You have to trust. You have to risk heartbreak. That's the only way you really touch life — or let it touch you."

These lessons shaped everything Hein did with Freedom. He trusted an apex predator to fly above packed stadiums. He trusted people to understand the deeper symbolism of their encounters. He trusted life’s uncertainty enough to build an entire career around a wild bird — and later, to mourn that bird’s passing with dignity, gratitude, and hope for what might come next.

In the end, Hein’s philosophy is both simple and profound:

Be present. Make it personal. Take risks. Trust deeply. Live fully.

A Legacy That Still Soars

In the quiet after Freedom’s final flight, in the stillness of the Center for Wildlife Education where echoes of wings once stirred the air, Steve Hein’s story, and Freedom’s — continues to ripple outward.

It is not a legacy built on spectacle, but on something far deeper: a lifetime of choosing presence over applause, trust over control, meaning over momentary fame. In every handshake at the Wildlife Center, in every child’s wide-eyed stare, in every graduate’s memory of a photograph taken with Freedom — the impact lives on.

For decades, Hein’s work was never just about wildlife education, or art, or falconry. It was about connection.

It was about reminding people that life is richer when you dare to step closer, when you risk feeling awe, loss, wonder, and love.

It was about showing that vulnerability is not weakness, but the purest form of strength.

Freedom’s story did not end with his passing, and neither does Hein’s mission. A new eagle waits in the wings now, beginning its long, patient journey. A new generation of students, visitors, and dreamers will look up and see not just feathers against the sky, but a symbol of resilience, trust, and hope.

And somewhere behind it all is Steve Hein.

The artist.

The falconer.

The storyteller.

Freedom’s plus one.

And above them all, forever riding the thermals of memory and meaning, soars a spirit too large to ever be forgotten.

Freedom flies on.